By Meghna Bal and Mohit Chawdhry

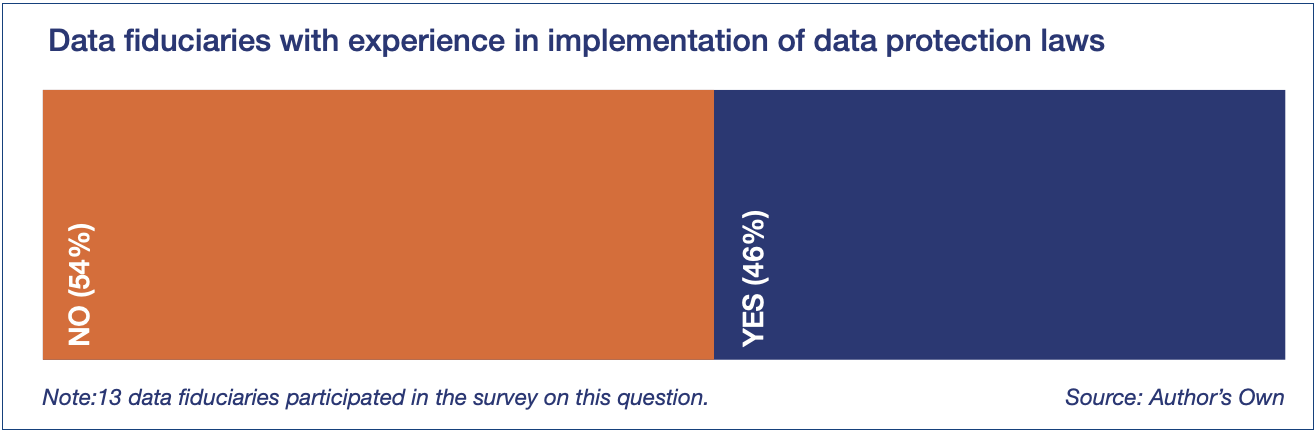

As we head towards the implementation of the DPDPA, it is vital to take stock of the compliance challenges data fiduciaries may face. This blog presents findings from our latest paper, which is based on a survey of 13 data fiduciaries and three subject matter experts. It finds that a majority of data fiduciaries have no prior experience in implementing data protection laws. While a majority have initiated discussions on compliance, progress is inhibited by the lack of rules under the Act.

Moreover, complying with certain obligations, such as presenting consent notices in 22 languages and obtaining verifiable consent from parents/guardians of children or disabled persons, will pose considerable technical and operational challenges for most fiduciaries. Resultantly, a phased and gradual approach to DPDPA implementation, supported by open and continuous communication and consultation between stakeholders, will prove vital.

In August 2023, the Indian Parliament passed the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA). Data protection legislation is crucial for giving digital product consumers control over their data. These laws also play a critical role in cybersecurity by encouraging organisations to protect personal data through a system of penalties and remedies. However, implementing data protection laws has proven to be not so easy a task.

These challenges have been identified in other regions, like the European Union, and often stem from operational and technical implementation issues, as well as difficulties in interpreting data protection responsibilities. To evaluate whether India’s data protection law would present similar challenges, we carried out a study where we interviewed 16 respondents, 13 businesses that collect and process personal data of their users and 3 experts. Our research presented some interesting results.

For starters, of the 13 data fiduciaries surveyed, 54 per cent had no prior experience with data protection law implementation in other jurisdictions, primarily firms with large user bases. Nevertheless, 85 per cent have started initial discussions on compliance with the DPDPA. Their readiness, however, is impeded by the lack of detailed rules that provide the practical framework for implementing many DPDPA provisions.

A majority of the provisions in the DPDPA rely on the introduction of delegated legislation to make the contours of compliance clear. Until this is done, it is impossible for data fiduciaries to begin any serious effort towards compliance.

The DPDPA requires data fiduciaries to provide users with notices that inform the latter of the purpose for which their data is being collected, how they may exercise their rights under the Act, and how they may make a complaint. The Act requires data fiduciaries to give users the option to access this notice in English or any language listed in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution, which includes 22 languages.

The ostensible objective of this requirement may be to ensure inclusivity to accommodate India’s linguistic diversity. However, this objective could be defeated for two reasons. One, some of the languages listed are spoken by a tiny fraction of the population. Illustratively, one respondent noted that Sanskrit is one of the Eighth Schedule languages; according to the last available census data, it is considered the mother tongue by less than .002 per cent of the population.

Secondly, preferences for languages that are not included in the Eighth Schedule may also lead to the exclusion of some data principals whose primary language is not listed in it.

Another issue related to the fact that the DPDPA requires data fiduciaries to obtain verifiable consent from the parent or the guardian of a child or a person with a disability. Some data fiduciaries raised concerns about the consent requirement for individuals with disabilities. They pointed out that the Indian Contract Act of 1872 does not recognise contracts made by individuals deemed to be of unsound mind.

According to Section 12 of the Contract Act, a person is considered of sound mind if they can understand and make rational judgments about a contract's impact on their interests. This criterion would apply only to those with severe mental incapacities in the context of disabilities. The corollary here is that the scope of the term disability under the DPDPA should be restricted to such persons.

However, the DPDPA does not specifically define "disability," leaving ambiguity about whether it covers all individuals with disabilities. Respondents found this lack of clarity problematic and potentially discriminatory against disabled individuals who are legally competent to enter into contracts.

Moreover, they expressed concerns that the current language of the provision might conflict with the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, which mandates that the government ensure that people with disabilities have the same legal capacity as those without disabilities.

Given these challenges, a phased and pragmatic approach to implementation is advisable. An official compliance period, akin to the two-year preparatory periods allowed in jurisdictions such as the European Union, Brazil, and Japan would give data fiduciaries the necessary time to adapt their operations to meet the DPDPA's requirements.

Our analysis suggests that most data fiduciaries would require more than 24 months to achieve full compliance, underlining the need for a structured and lenient implementation phase. Moreover, simplifying certain compliance obligations and offering clear definitions and guidelines, particularly for ambiguous terms and requirements, would significantly reduce the compliance burden on data fiduciaries. For example, clarifying the scope of "disability" and streamlining consent notice requirements would make the compliance process more straightforward.

Finally, fostering an environment of collaboration and dialogue between the government and data fiduciaries is crucial. Implementing mechanisms for consultation and feedback on the Act’s implementation can help identify and address practical challenges in real-time.

Opening consultation processes for the rules enacted under the DPDPA, with sufficient time for stakeholders to provide input, would ensure that the regulatory framework is both effective and reflective of the diverse needs of the digital ecosystem.

As India stands at the threshold of a new digital privacy era, successfully implementing the DPDPA will require concerted efforts from all stakeholders involved. By adopting a phased, consultative, and flexible approach, and by paying heed to the operational and compliance challenges highlighted by data fiduciaries, India can navigate the complexities of this transition. This will not only uphold the rights of individuals but also support the growth and innovation of the digital economy.